I wish none of this had ever happened. Sometimes I thank God that it did.

|

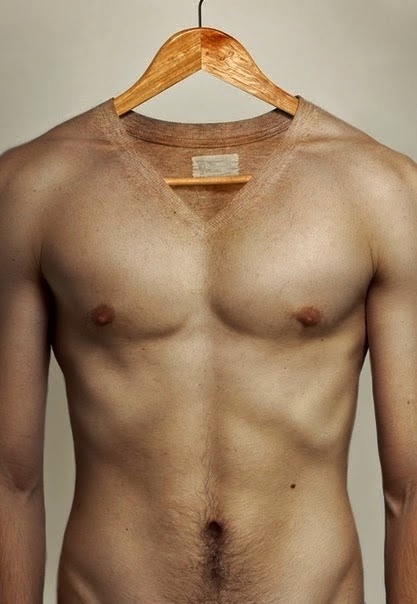

| Dmytro Kapitonenko - Athletic suit (source) |

The rest of my bigotry I learned from pantomime: limp wrists and exaggerated sashays from mocking church members; phrases that lifted out of natural speech into show-tune lilt—“Oh, you shouldn’t have”; church petitions that had to be signed in order to keep our country safe from “perverts.” The flash of neon spandex, the rustle of a feather boa, the tight ass shaking for the camera: What I did manage to see on TV just seemed further proof that being gay was freakish, unnatural.

To be counted a sissy was one thing; to be counted a sissy and an Arab sympathizer was another. To be counted a sissy and an Arab sympathizer would pave the way for others to finally detect the attraction I felt to men. And when they discovered that secret, nothing would stop them from retroactively dismissing each detail of my personality, each opinion of mine, as mere symptoms of homosexuality.

After my parents decided to move their old television into my bedroom, I used to stay awake to watch the midnight news so I could imagine there were other people still awake, other people doing things at that moment, and I would think about how God wouldn’t leave so many people behind and I would feel safe for a few minutes.

After only a few questions, I no longer remembered what I felt. It was true that I was never any good at sports. It was true that I never liked to toss the ball with my father in the front yard. Yes, I might have caught my father’s initial pitch, but I’d eventually thrown down the baseball glove and let the ball roll out of its leather grip. But did that mean I hadn’t enjoyed the way the grass felt beneath my toes? Did that mean I hadn’t loved the feel of the hot sun on my face—hadn’t felt my father’s voice as a warm vibration passing through my chest? I could no longer be sure.

Even if you know the person—especially if you know the person—rape, and the memory of it, becomes a blinding flash. A brush against something bigger than yourself. Sometimes the experience takes the form of a divine visitation, such is our need to displace the reality of it. [...] I might remember, in ultraexposed detail, the swirl of wood grain at the base of David’s bunk, the sound of the hallway doors closing one after another outside his room as my fellow freshmen returned from their nights of heavy drinking. But I would not remember the act itself.

A few hours passed, and then it happened. At first, it was like baptism. I felt my body go under, but someone else’s hands urged me below the surface. Like my baptism, I had worried what it would feel like, what I would be asked to do, the exact logistics of the act. Would I feel differently? Would I be changed forever, as people said I would?

I worried about how my body would look. I worried about the stretch marks. Even as he forced my head down, I worried that I might not do it right. Even as I gagged and struggled, pulled at the hairs on his calves, trying to do anything that would make him stop, I worried about upsetting him.This was not what I wanted it to be, I thought.

A minute of silence passed. Then, feeling I could no longer keep it inside, I burst into tears and told her it was true, that I was gay. Saying the word aloud made me feel sick inside, and I wondered if what David had forced me to swallow had somehow grown inside of me, rendered me permanently gay.

But where was Jesus in all my time at the facility? Where was His steady nail-scarred hand? The prayers I continued to recite each night became even more desperate and meaningless. Please help me to be pure. Please-help-me-to-be-pure. Pleasehelpmetobepure.

Nowhere. Nowhere was the answer.

As Cosby spoke, I wondered what it felt like to see yourself reflected in every movie, to have friends and family constantly dropping fun little hints about your love life, to have the world open up to you in all its magnificence. What did it feel like to not have to think about your every move, to not be scrutinized for everything you did, to not have to lie every day?

I couldn’t find the nerve to tell them what my friend had done. David had trumped me: The knowledge of my homosexuality would seem more shocking than the knowledge of my rape; or, worse, it would seem as though one act had inevitably followed the other, as though I’d had it coming to me. Either way, our family’s shame would remain the same.

I had learned by now that there was a cumulative effect to beauty. If people already saw something as beautiful, the object of their affection would continue to receive all possible praise and attention. Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose, Gertrude Stein, my new favorite poet, quipped. Naming something beautiful made it so. I’d seen this in the way the church spoke of marriage as a sacred institution and in the ONE MAN + ONE WOMAN bumper stickers people sported on their vehicles, the same ones my father would hand to any customer passing through his dealership’s service department.

“How do you feel?” my mother said. Her hands were firmly fixed at ten and two on the wheel. This vigilance, this never taking a risk when you didn’t have to.

“I’m fine.” We’re all faking it.

“We can stop again if you need.”

“That’s okay.” It’s just that some of us are more aware of it.

Often, it felt like a small victory to realize that another point of contact had lost its hold on me. I was in control of how quickly I lost the weight, and it felt good not only to feel the past leaving my body—all that fat like rings of a trunk now narrowing, disappearing—but also to see the shock on people’s faces, the lack of recognition at first glance, the double take. I was a different boy.

I returned to the hotel room and doubled over near my cot, nearly vomiting from exhaustion and fear. Who was I? Who was this man who cursed God? Better yet, who was God? Had He abandoned me or had He never existed in the first place?

My mother’s face soon relaxed into a sweetness I had known when we used to go shopping in the city together. And as we traveled farther from the hotel, we managed to wrestle free of the present, to slip into an alternate future that only a few moments ago had seemed impossible.

It wasn’t that she had given up on the therapy. In the hour that followed, my mother would ask me at least half a dozen times if I thought I was going to be cured. We just decided to ignore the details for the moment.

I came to therapy thinking that my sexuality didn’t matter, but it turned out that every part of my personality was intimately connected. Cutting one piece damaged the rest.

“My heart isn’t separate from the rest of me.” He took another hit. “This is just me. All of me. See?” [...] “Why would God give me so many feelings if he didn’t want me to feel them? Why would God be such a jerk?”

Garrard Conley - Boy Erased (Riverhead-2016)

Commentaires

Enregistrer un commentaire

Si le post auquel vous réagissez a été publié il y a plus de 15 jours, votre commentaire n'apparaîtra pas immédiatement (les commentaires aux anciens posts sont modérés pour éviter les spams).