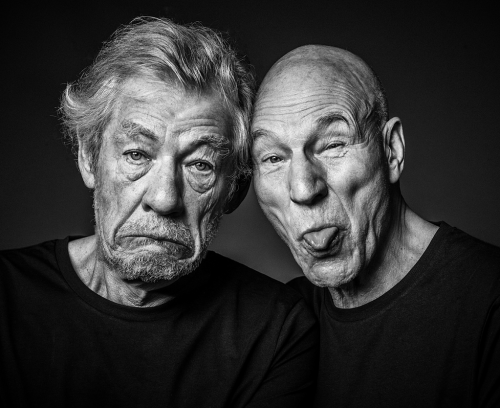

Double messieurs

|

| Sir Ian McKellen & Patrick Stewart ©Andy Gotts |

Wendell et Frank sont deux octogénaires qui ont toujours vécu l’un pour l’autre, à l’écart du monde, se faisant passer pour des frères si besoin.

Quand la santé physique et mentale de Franck dégénère subitement, Wendell se retrouve seul pour y faire face.

Je suis à mi-parcours de Hide, de Matthew Griffin, et je me régale; on navigue entre le présent de ce vieux couple déclinant et le passé, au moment de leur rencontre : c’est tendre, caustique, drôle, triste…

Peut-être parce que j’ai vu quelques épisodes de Vicious, la série dans laquelle il forme avec Derek Jacobi un couple de vieux homosexuels, dans mon esprit, Frank a les traits de Ian McKellen. Il serait parfait dans le rôle, si le roman devait être adapté au cinéma.

“Looks just like she’s asleep,” Frank said, his voice wavering, uncertain. He squeezed my hand, quick and furtive, and let it go. “Don’t she?”

It’s all one big waste of time, embalming. A good professional mount will last you a thousand times longer than pumping somebody’s veins full of formaldehyde and painting them over with makeup will. Formaldehyde might keep them for a while, but you’ve still got to put them in the ground sooner or later, and soon as water gets into that coffin—and it will, no matter how hard you try to keep it out, no matter how many nesting Russian dolls of caskets and vaults you wrap around somebody, water always finds its way in—it washes the chemicals right out and the body starts to decompose so vehement and rapid and anaerobic you’d think it was making up for the late start. You ought to just skip all the moaning and crying, get them in the ground a little quicker, and save yourself the trouble.

And not once in my life have I seen an embalmed corpse that looked as if the person was sleeping. I don’t know why everybody insists on saying that.

“She does,” I said. “She really does. She looks just right.”

Even in the army, even in the showers, surrounded by all those men in various stages of filthiness and nudity, with aching muscles and grass stains on their knees and the puddle over the clogged drain turning milky with soap as it widened toward their feet, nobody ever knew. Not the slightest inkling. He always prided himself on that.

The secret, he said, was that you had to look a little. Not looking was the most suspicious of all. It meant you cared. So you learned to move your eyes over their bodies without really seeing them, he said, to look just long enough and then away: the way you do to look at the sun, real quick, before it can burn a green hole in everything you’d see after.

I was never quite as adept at it. There was some softness in me that betrayed itself in ways so subtle even Frank couldn’t tell me exactly what they were. My own customers always looked at me a little askance, even as they brought me their pheasant and their fox, as if there must be something wrong with me to want to render this service they themselves wanted rendered, as if I, too, might secretly be dead as the animals on the wall, and just made up to appear otherwise.

The sky stretched across his shoulder to his collarbone, from which a flock of birds of all kinds, swallows and sparrows, hawks and owls, bluebirds and red, emerged, their bodies and beaks overlapping, the sky’s darkness fractured and furling into them, drawn into the curves of their wings and the feathers of their tails, dragged with them as they strained toward his breastbone. The blond hair on his chest blurred the lines of their bodies. Their wings beat against my lips.

Above his belt was a tiny, still-forming scar, shiny and tender as a plant stem, where shrapnel had grazed him just enough to split the skin. He leaned back as I worked my fingers underneath his waistband, he held his breath as I found it there, that warmest part of him, and pulled it free, barely curved like the branch of an antler, long and hard, the velvet just rubbed away from the bone. Its musk was unruly, wild, the kind that lingers on bark, marking to whom the land belongs. I felt the heavy pound of his heart inside it.

He wrapped his arms around my waist and dragged my hips to his; he pushed my legs up, my knees to my chest, but held himself just slightly above me, squinting a little, looking at me much longer and more closely than I was accustomed to, and in a way no one had ever looked at me before: as though he were seeing, all of a sudden, the answer to a question he’d been asking for a long, long time.

In the last thin film of evening light, he blushed, hives rising in patches up from his collarbone, dappling red the skin of his throat. And then he grinned, open and expansive, and in that moment he seemed happier, more animated, more alive, than anyone I had ever known.

He ran his thumb along my eyebrow. It had been years since a hand had touched my face.

The birds rode the ragged currents of his breath, rising and falling. Trembling, he rested against me all his heavy weight, and pressed his face into my hair, and gasped as he pushed slow and straining inside me, where he waited, rigid and pulsing and still, until my body believed he was just another part of itself.

Matthew Griffin - Hide (Bloomsbury-2016)

Commentaires

Enregistrer un commentaire

Si le post auquel vous réagissez a été publié il y a plus de 15 jours, votre commentaire n'apparaîtra pas immédiatement (les commentaires aux anciens posts sont modérés pour éviter les spams).